China’s stock markets had their shortest trading day to date on Thursday – not even half an hour – capping off a frantic four days of market turmoil that cascaded across the globe.

The mechanism

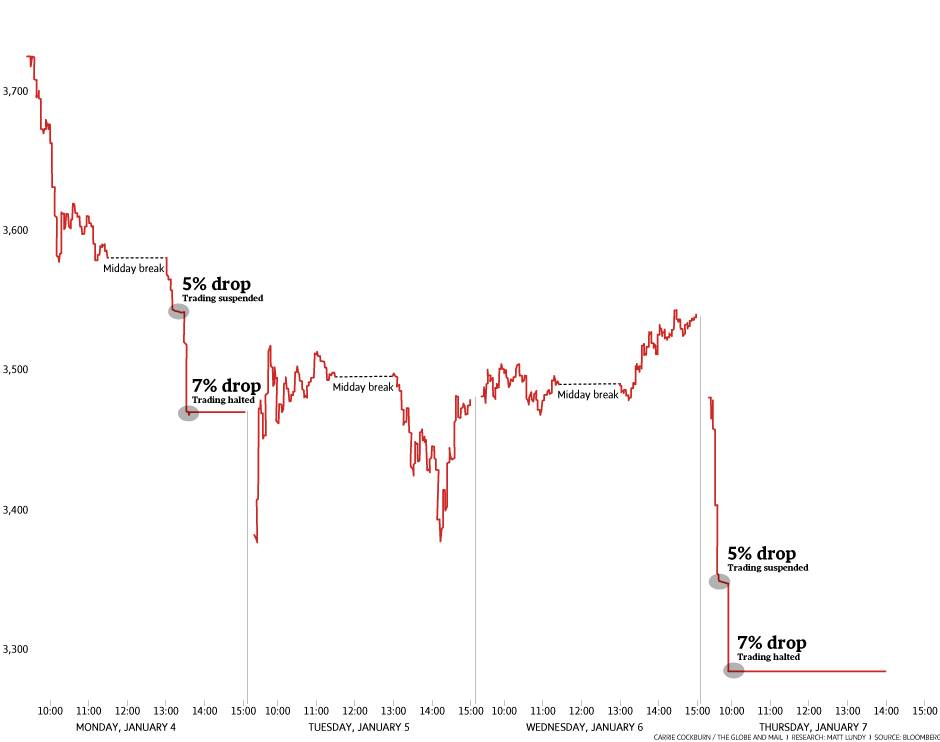

China’s new circuit-breaker system is shaping up as a short-lived idea. Just three days after its debut, the system has been scrapped by China’s securities regulator, at least temporarily. Circuit breakers are a mechanism used to tap the brakes on volatile trading. Of course, big swings are nothing new for China’s markets. The CSI 300, an index of the largest firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen, plunged nearly 15 per cent in July of last year, during a particularly volatile stretch. Under China’s plan, a 5-per-cent swing to the CSI 300 in either direction would trigger a 15-minute suspension of trading. Further movement to a 7-per-cent limit would spell an end to the day. Stock selloffs triggered the mechanism in two of the opening four trading days of the year. On Monday, trading was halted with about 80 minutes remaining in the session. Thursday, however, was truly stunning. Just under 30 minutes into the session, the day was over.

China’s circuit-breaker system was meant to safeguard markets from steep sell-offs, the likes of which can be seen in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Instead, the mechanism itself may have played a leading role in this week’s downturn. “The circuit-breaker system has been criticized because the 7-per-cent level at which markets are halted appears to be acting as a target for sellers,” said Jasper Lawler, market analyst at CMC Markets, in a research note. Indeed, multiple reports from Thursday spoke of traders working hard to offload stocks before the day’s quick conclusion. For its part, China’s securities regulator shifted blame away from its now suspended system. “The circuit-breaker mechanism was not the main reason for the market slump,” Deng Ge, a spokesman for the China Securities Regulatory Commission, said in a statement. “It just didn’t work as anticipated based on actual situations. The negative effect of the mechanism outweighed its positive effect.”

Aftershocks

China’s market turmoil has spread beyond its borders. The S&P/TSX composite index of the largest firms listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange sank 2.19 per cent on Thursday. With that decline, it has now fallen into bear territory, plunging more than 20 per cent from a high in September, 2014, and ending a bull run that started in 2013. The S&P 500 index of the largest U.S.-listed firms fell 2.37 per cent on Thursday, while the Nasdaq composite dropped 3.03 per cent on the day. The opening of China’s markets has become appointment viewing for North American traders looking to get a sense of the day ahead. If this week is any indication, China has set an ominous tone for 2016.

Slowing growth

China’s growth prospects are weighing on investor sentiment. Following two decades of explosive growth, the country’s economy is shifting into slower gear, raising concerns for the global outlook. Beijing announced in November a 6.5-per-cent target for annual economic growth from 2016 to 2020 – a goal that some consider unattainable. The most recent reading on gross domestic product, for the third quarter of 2015, saw a 6.9-per-cent expansion from a year earlier. It was the first time since the global financial crisis that China’s economic growth slipped below the 7-per-cent mark. Less than two weeks from now, GDP figures for the fourth quarter will be released, giving investors some indication of China’s economic health heading into the new year. Look for those numbers to make their impact – whether positive or negative – on the markets.

Triggers

Two contributing factors to this week’s tumult are tepid manufacturing numbers, along with a devaluation to China’s currency, the yuan. China’s factory activity contracted for a 10th consecutive month in December, according to a private survey released Monday, signalling weakness in a crucial pillar of the Chinese economy. On Thursday, China’s central bank guided the yuan lower at the quickest pace since a surprise devaluation in August. Weakening the currency, in theory, would give exporters a boost by making their goods cheaper. “It’s probably inevitable that China’s exchange rate needed to fall to reflect its slowing economy, but it’s the speed of the current devaluation that has investors unnerved,” said Jasper Lawler of CMC Markets in a note. “A slower pace of yuan devaluation would at least give investors and European exporters a chance to adjust to the new normal.”

But wait …

But what if the China concerns are overblown? After all, we’re talking about a country with economic-growth rates that just about any industrialized nation would pine for. Following Thursday’s turmoil, research firm Capital Economics struck a bullish tone in a note. “Over all, the latest economic data do not point to a slowdown in activity, credit growth has accelerated and more policy stimulus is in the pipeline.”