When he can't find work in his hometown of Hamilton, Eric Banfield heads west. His 11 years as an ironworker have taken him from Potash mines in Saskatchewan to skyscrapers in downtown Calgary to the Athabasca oil sands in northern Alberta.

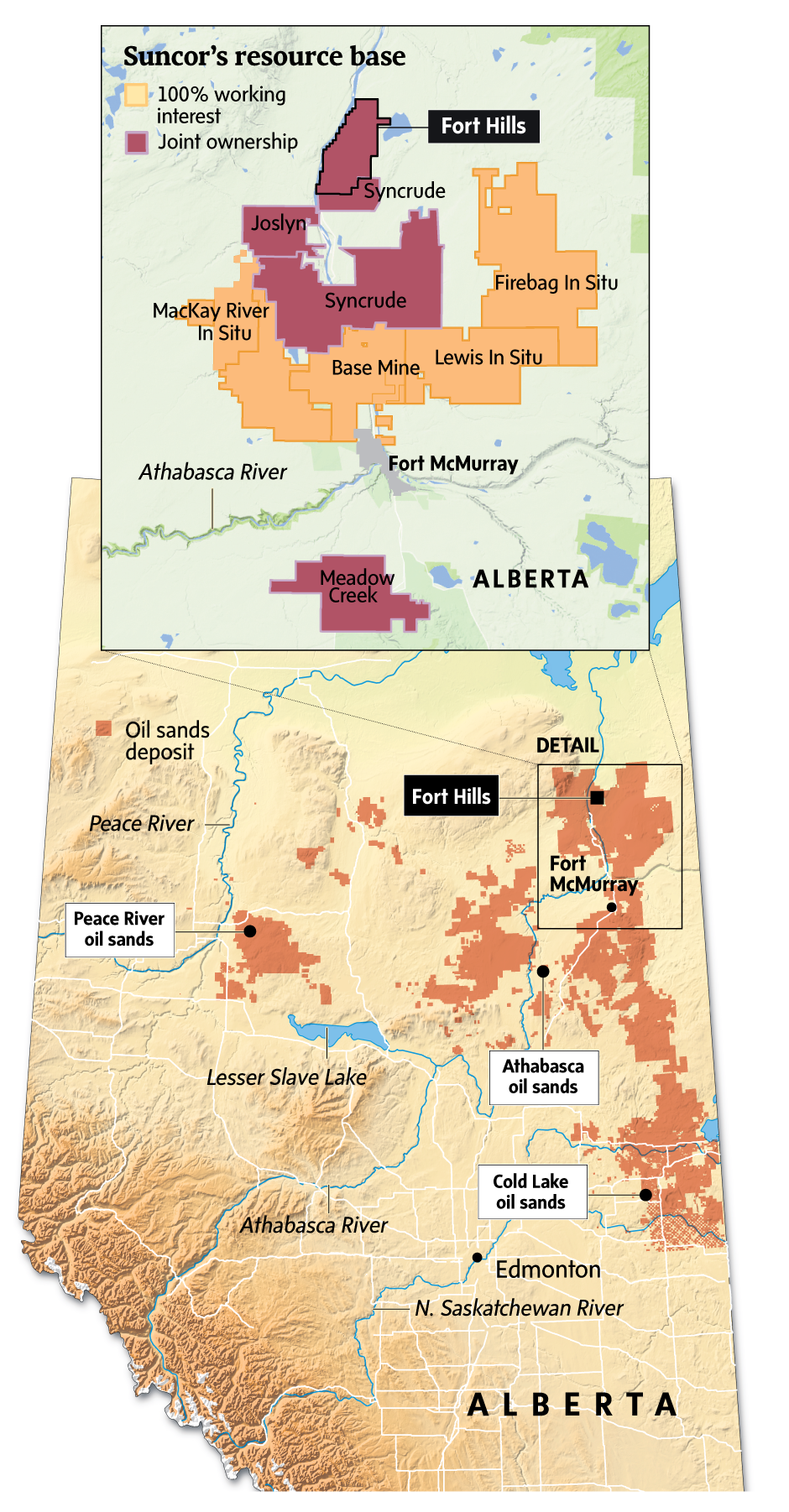

For the last eight months, he has been a foreman on contract at Fort Hills, the bitumen mine under construction by Suncor Energy Inc. and its partners about 90 kilometres north of Fort McMurray, Alta.

"When there's not work at home, all of us kind of count on jobs out here," says Mr. Banfield, seated in a dining hall at a Fort McKay work camp following a 10-hour night shift.

But Mr. Banfield, 38, says it's not clear how much longer he can count on work at Fort Hills, or anywhere else in the oil patch for that matter.

"The job board is looking pretty bleak."

The same could be said about prospects for new big-ticket oil sands developments in Alberta. After more than a decade of non-stop building, the era of the oil sands megaproject is coming to an end.

Over the past 10 years, energy companies have gone on a $227-billion capital spending spree to build massive industrial complexes that tap one of the world's biggest oil reserves. Now, after more than two years of slumping oil prices and excess global supply, the last of the giant oil sands construction projects – Fort Hills – is nearing the finish line. The first oil is scheduled for the last quarter of this year.

An aerial shot of the Fort Hills oil sands project. (Phoenix Heli-Flight)

Canada's oil industry has already been battered by the oil downturn, as companies slashed tens of thousands of jobs and scrapped spending plans in a bid to cut costs and stem huge losses. The steep cutbacks plunged Alberta into recession. Still, some companies pushed forward with a number of complex, supersized long-life projects that were deemed too advanced to halt.

But what's coming next will be another jolt of pain to the energy sector, and the economy. As the oil sands construction frenzy runs out of steam this year, workers will no longer be able to look forward to the next series of big projects, and a broad spectrum of companies that had long flourished from the growth of the oil sands is now seeing opportunities dry up.

"It is not going to be like it was," says Bruce Moffatt, business manager for the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 955, which represents thousands of mobile-equipment operators in oil sands construction and operations. "We've had 10, almost 15 years of people being able to go to one job to the next with no periods of unemployment between," says Mr. Moffatt. "We're not seeing that any more."

Work is rapidly wrapping up or has recently ended on a string of major projects in Alberta that had carried on through the oil downturn. North West Upgrading Inc., in partnership with Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., is spending about $8.5-billion on a new refinery north of Edmonton, expected to be up and running this year. Canadian Natural is putting the final touches on a third production phase at its Horizon bitumen mine. Imperial Oil Ltd. started pumping crude from the second phase of its massive Kearl mine in mid-2015 after spending $8.9-billion.

But today one project stands out as a monument to the unrestrained ambition – and soured economics – of the great oil sands building boom: Fort Hills.

At $15.1-billion, the mine's construction cost is big even by oil sands standards. The project will extract 110 million tonnes of oil sand per year, and produce 180,000 barrels of bitumen a day. Some 5,000 construction workers currently toil away on site, a figure that will fall by more than half once construction is complete and production begins late this year.

Fort Hills is literally at the end of the road of oil sands projects. It's a 90-minute drive northbound on Highway 63 from Fort McMurray, past a series of other oil sands operations, past the turnoff to the Fort McKay First Nation and across the Athabasca River on the so-called Bridge to Nowhere. From the parking lot of the Fort Hills main gate, the vista is a massive mine taking shape, including conveyors, tanks, and large vehicles moving people and supplies around the sprawling property. Go further past the main gate, and you will leave Highway 63 and hit the winter road to Fort Chipewyan, Alta. and Fort Smith, NWT.

There are only so many oil sands deposits worth building a massive mine for, and Fort Hills is among the last stretches of land rich in close-to-the surface bitumen.

"The big oil sands stuff – the golden years may be over," says Neil Camarta, the former oil sands executive and engineer who became a specialist in building oil sands mines and upgraders. "The ones with good dirt are already under the plow. Fort Hills was the last one that has good dirt."

The project is a vivid testament to the era of bumper budgets and $100 (U.S.) crude, and will likely stand as a bookend on the decade-plus oil sands boom in northern Alberta.

Owned 50.8 per cent by Suncor, 29.2 per cent by Total SA and 20 per cent by Teck Resources Ltd., Fort Hills has been dogged by skeptics and false starts from the beginning.

In the mid-1990s, the rights were held by financially troubled Solv-Ex Corp. of Albuquerque, N.M., a company that tried and failed to pump crude with an unproven technology and was later fined by U.S. securities regulators for misleading investors. Wichita, Kan.-based Koch Industries Inc. bought the project in 1997.

By 2001, its Calgary-based arm, called TrueNorth Energy LP, sketched out plans to develop a $2-billion extraction project with partner UTS Energy Corp. to pump out 95,000 barrels per day starting in 2005. The blueprint was scrapped two years later, however, and Koch sold its interest to UTS. In 2005, Petro-Canada, later acquired by Suncor, bought 60 per cent of the project from UTS, and became operator. A predecessor of Teck bought a 15-per-cent interest in the same year. UTS was bought by French giant Total in 2010.

Suncor finally agreed to build it in 2013, assuming oil prices of $95 a barrel. The company pegged the annual rate of return at 13 per cent.

Kelly Cryderman/The Globe and Mail

But oil's collapse to around $50 or so a barrel has clobbered those expectations, reviving long-standing questions about the mine's economic prospects. Already, partner Teck Resources Ltd. has taken a significant writedown in its 20-per-cent interest in the project.

And some industry experts say Suncor's forecasts about Fort Hills' projected returns are far from realistic.

Oil prices are only around half the price that would be needed for the huge project to break even over its lifetime, including upfront construction costs, according to some estimates. "It looks like it needs in excess of $100 oil to break even," says Rob Bedin, analyst at RS Energy Group in Calgary. The project was based on "a view or a belief that oil prices will rebound," Mr. Bedin says. "That view is obviously not shared by many."

Similarly, Edinburgh-based consultancy Wood Mackenzie calculates an average oil price of $95 for Fort Hills to break even.

Others have a more favourable outlook. Bank of Montreal analyst Randy Ollenberger pegs the rate of return at 10 per cent with an oil price of $65, and closer to 2 per cent at $40 oil. Suncor has improved the economics somewhat by purchasing an additional 10-per-cent stake from partner Total at a hefty discount, he notes. And the project will likely generate positive cash flow at $50 oil.

Still, the huge mine serves as an outsized reminder of the "crazy decade" that preceded the oil-price crash, a period when oil sands projects became synonymous with cost blowouts and meagre shareholder returns, says Jean-Michel Gires, president of NextTier Energy Solutions and Total's former Canadian head. It is an experience the industry is not eager to repeat. "Everybody has learned that something was wrong, for sure. If you meet somebody who can tell you that was fantastic, that was exactly what we wanted to do, we have been very pleased with the results and we'd like to do that again, call me. I don't think I know anybody in that category," says Mr. Gires. "Nobody has been pleased."

The process: From extraction to shipment

Before oil sands ore can become crude oil ready for shipment, it must first go through a complex extraction process involving crushing, sifting and filtering. Fort Hills will use a special paraffin-based solvent to help remove solids from the bitumen, making it ready for upgrading into a final marketable product.

There were worries about the scope of Fort Hills early on. In May, 2011, Christophe de Margerie, the late chief executive officer of Total, arrived in the mountain resort of Banff, Alta. He was not there for the scenery.

Six months earlier, Total and Suncor had struck a multibillion-dollar deal to jointly develop Fort Hills, another mine, and a processing plant.

Mr. de Margerie met with then-Suncor chief executive officer Rick George and its chief operating officer at the time, Steve Williams. The discussion was frank, according to a person who attended the meeting. "It was a big bet – a huge bet. Three major projects like that more or less in the portfolio at the same time, huge co-ordination issues, and two companies never having worked together."

Mr. de Margerie was concerned the partners had bitten off more than they could chew. Total itself had spent billions on undeveloped oil sands leases, and was eager to see some payback. It was an early sign of anxiety for an industry that had struggled with high costs and thin returns even when oil prices fetched more than $100. Two of the three projects – Joslyn and Voyageur – were ultimately scrapped, signalling the age of the bitumen megaproject was nearing an end.

Fort Hills' owners insist the project is still a jewel. The mine will churn out cash flow for years to come with minimal production declines, officials say. Suncor's Mr. Williams, now chief executive, says it's Fort Hills' long production life of more than five decades that justifies the investment, and the project will be able to generate free cash flow with oil prices at $40 or even lower. "It's a very attractive project in the current environment. It gets even better as the cycle starts to turn," Mr. Williams says. "This is effectively an annuity for 52 years."

With a mine life that long, Fort Hills is "going to have two or three good years several times when it gets all of its capital back. And as long as its operating cash costs are low enough that it's going to go throughout the cycle, then you end up with a good-quality asset," agrees Teck chief executive Don Lindsay. "We're pretty excited about that."

And when Suncor finally agreed to build it in 2013, investment-to-date at Fort Hills had already exceeded $4-billion, notes GMP FirstEnergy analyst Michael Dunn. "So the go-forward economic decision was different than if you were starting from scratch," Mr. Dunn said.

Watch: Take an aerial tour of Fort Hills

Like its industry peers, Suncor has scrambled to bolster finances stretched by weak oil prices. It has put off investments in some steam-driven projects, cut more than 1,700 staff, sold assets and clawed back operating expenses – all while pouring money into construction of two megaprojects located at opposite ends of the country.

One is Hebron, a $14-billion (Canadian) project offshore Newfoundland and Labrador in which Suncor has a 21-per-cent interest. The other is Fort Hills. Suncor refused to slow or halt construction at the northern Alberta project, despite diminishing returns and concerns over increased leverage.

The project was a major preoccupation within Suncor's executive ranks during the past rocky year or so for the company. The Alberta wildfires last year shut some oil operations for weeks, sapping cash flow already squeezed by languishing oil prices. A weak Canadian dollar had put upward pressure on Fort Hills' costs, which are tied to a far-flung supply chain, including steel fabricators in India, China and South Korea.

Under financial pressure, Suncor decided last year to issue $2.9-billion of shares and sell some non-core assets such as a lubricants unit – necessary steps to keep funding flowing for the cash-gobbling Fort Hills and Hebron projects. The company even eliminated its in-house air service, resulting in the planned sale of three Bombardier CRJ jets.

Despite Suncor's resolute commitment to Fort Hills, one executive privately admits the company wouldn't sanction the project in today's market, since most industry players now believe the days of $100 (U.S.) crude are over. Analysts and industry executives expect ample supplies of U.S. shale crude, and uncertain demand, to keep oil prices well under triple-digit highs of the the past.

Last fall, Imperial and its U.S. parent company, Exxon Mobil Corp., warned they may have to write down billions of barrels of reserves at their Kearl bitumen mine should oil prices stay low. The partners have spent $21.8-billion (Canadian) developing the project.

It all points to a much diminished future for Alberta's deposits of tarry bitumen, which have lost ground to massive shale reserves in North Dakota and Texas that can be developed more quickly and at a fraction of the cost.

Certainly, no one is predicting big oil sands projects will shut down, and spending in the oil patch has recently increased along with firmer oil prices. Cenovus Energy Inc., MEG Energy Corp. and Canadian Natural have all restarted work at smaller, steam-driven projects in recent months. The two-year push to drive down outlays for operating oil sands projects has netted cost reductions of 30 to 35 per cent, said Mr. Dunn at GMP FirstEnergy. Construction expenses have also dropped."The cost structures have come down way, way, way more than any of us would have imagined possible," he said.

Opposition to oil sands expansion has stalled the development of new pipeline capacity, and producers are concerned about access to the most lucrative global crude markets. But this week's move by U.S. President Donald Trump to revive prospects for the Keystone XL pipeline to be built has added new optimism that oil sands production will be able to increase in the coming years.

Even so, the industry is increasingly dominated by a handful of large players and new developments tailored for squeezing more crude from existing assets without huge new capital costs. That necessitates fewer workers.

The shift has profound implications for a region once considered a Shangri-La by some of the world's biggest oil companies. Although crude prices have improved, cash-poor Alberta is expected to grow at a moderate clip – "well shy" of the more than 5-per-cent pace seen in the five years through 2014, according to Bank of Montreal economist Robert Kavcic. He predicts spillover effects will hit weakened commercial and residential real estate markets, and weigh on government finances already groaning under an increased debt burden.

All kinds of energy-related businesses are now feeling the pinch. Edmonton-based construction firm PCL Constructors Inc. will have 2,500 employees and subcontractors on site at Fort Hills early this year – making up about half the construction work force on site as the project nears completion. The employee-owned group of companies has enjoyed years of strong business from major oil sands projects, including Imperial Oil Ltd.'s Kearl site, and ConocoPhillips' and Total's Surmont site. But now the future is less clear. "For sure we're very worried," says Ian Johnston, chief operating officer of PCL's heavy industrial division. "The oil sands have been a big backbone of our business."

Similarly, the Bouchier Group, a service company based in a tiny industrial park just outside the aboriginal community of Fort McKay, has been a beneficiary of the virtually non-stop construction at Canadian Natural Resources's Horizon site, about 25 kilometres north on a forested highway. The private family firm has also won longer-term contracts with the oil-sands company going back a dozen years. The jobs included facility maintenance, road grading, and other preparatory work associated with big construction projects. "It's been great for a small, local contractor like us," said Nicole Bourque-Bouchier, chief executive officer and co-owner.

Today, the Bouchier Group's profit margins have been squeezed, and the end of construction at Horizon means she will have to lay off or find new work for at least 100 of her 800 employees. With less overall activity, however, there is less maintenance work to go around, and more companies are competing for the same jobs. "Now everybody – everybody from being small, local, and aboriginal to the multibillion, worldwide companies, are all fighting for the same contracts," Ms. Bourque-Bouchier says.

Another measure of the shift is severe cuts at Calgary engineering firms. Global giant AMEC Foster Wheeler PLC helped design the tailings management program at Fort Hills. But it has chopped staffing levels in Alberta by 30 per cent over two years as its backlog for new bitumen projects shrunk "to next to nothing," says Thomas Grell, who oversees the company's oil and gas business for the Americas. He has no illusions that the sector is poised to revive big spending plans any time soon.

"I wish it would, but I don't see that," he says. "This will be a flat-ish market for a long time."

Is the megaproject era over forever?

Suncor's Mr. Williams says it will be years before anyone contemplates building something on the scale of Fort Hills from scratch.

"I wouldn't say it's the end of the road," Mr. Williams says. "I would say there's a pause on those things for probably the next five to 10 years."

With a file from reporter Brent Jang in Vancouver

FURTHER READING: