Peter Pocklington's house lies in a gated community in the California desert. The Spanish-style bungalow he shares with his wife of 43 years is on a street lined with tall, impeccably spaced date palms. There are cactuses with sharp quills in the roundabouts, and golf carts parked outside nearly each million-dollar residence. In the distance, jagged mountain peaks fade from view like a Lawren Harris canvas.

Hockey's original rock-star owner has a deck that overlooks an emerald fairway along one of Palm Desert's private golf courses.

Hummingbirds flit around the pool and hover over a hot tub fed by a cascading waterfall. The home is elegant, but more understated than his previous address at the nearby Vintage Club. There, Pocklington had a helipad and a house with a retractable roof. Bill Gates, Charles Koch and Philip Anschutz were among his neighbours.

The eccentric swashbuckler who once owned the Edmonton Oilers lives behind a black wrought-iron gate and a trellis wrapped lovingly with magenta bougainvillea. He is guarded about privacy so one approaches cautiously, pausing in front. From inside, his wife, Eva Pocklington, calls out.

"Come in," she says breezily. "We have been expecting you."

There is a zebra-skin rug inside the front door. Valuable prints of Mick Jagger by Andy Warhol, once confiscated by the FBI, line the living room wall. A Marc Chagall painting hangs in one corner. Inuit sculptures rise from the floor. An affectionate tabby named Sophie, rescued after Eva saw its picture outside a supermarket, cuddles up to a stranger and purrs.

"We used to live in the Vintage, but this is much better for me," Pocklington says, swallowed up as he settles into a couch in his living room. "I really try to take a lower profile here. It is kind of nice to hide. Nobody knows I am here."

Revered and reviled, Pocklington once presided over one of the greatest dynasties in sport. It has been 20 years since he sold Edmonton's NHL team and fell from grace as one of Canada's most infamous businessmen. At one point, his empire exceeded more than $2-billion in sales, and included massive real-estate holdings, one of Canada's largest trust companies, chicken-processing plants, food-processing firms, and a beef– and pork-packing house. None of that brought as much satisfaction and fame to him as the Oilers.

When Pocklington traded Wayne Gretzky to the Los Angeles Kings on Aug. 9, 1988, it left the hockey world in disbelief.

Ray Giguere/CP

He won five Stanley Cups as the club's owner, but as an entrepreneur left a trail of debt and legal travails in his wake. The financial carnage included the Alberta government, which nearly three decades later is still trying to collect interest accrued on a $55-million loan.

Ever defiant, Pocklington is trying just as stubbornly to negotiate a settlement.

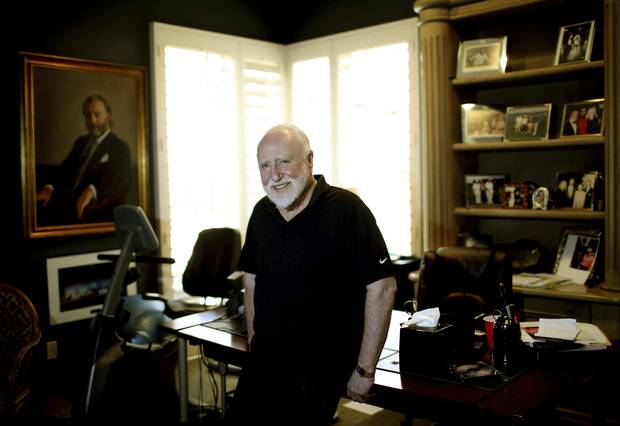

He is 75 with a neatly trimmed Papa Hemingway beard. He is charming and handsome, with painted blue eyes and a booming, baritone voice.

A maverick to some, to others he is the devil in disguise not just for his hockey dealings. It took nearly 30 years for fans to forgive him for trading Wayne Gretzky. In 2014, he received a standing ovation at Rexall Place during a reunion celebration of the Oilers' first Stanley Cup team. Tears pooled in his eyes.

"Thank you, Edmonton, thank you," he said that October evening. "I wasn't sure what was going to happen. As you can imagine."

Over the course of a couple of hours, his house phone and cell phone ring continuously. As he pads around, he talks about his triumphs and failures. Voice low, he mentions a project he believes could make him billions. He won't discuss details publicly.

If his life has taken awkward turns, he remains constant: undaunted, wily, and an unceasing adventurer. He has always been a dreamer, though some would say schemer is more accurate. He peppers conversations with quotes from Shakespeare and punctuates them with profanity. He is Don Quixote, dropping the occasional F-bomb as he tilts at windmills.

"I like Errol Flynn," he says, gesturing like a Musketeer and making the whoosh-whoosh sound of a sword slicing through air. "It is so much easier to go through life being an optimist. In fact, I really don't like being around people who aren't. They drag me down. I am not interested in being dragged down, ever."

Pocklington acquired and sold more than 50 companies

Peter Pocklington was born in Regina and grew up in London, Ont. According to his 2009 biography, I'd Trade Him Again, he exhibited early signs of being an operator and salesman.

At 5, he picked cherries, placed them in bottles filled with water, and sweet-talked neighbours into buying them, passed off as his mother's preserves. When he was 16, he sold his dad's Olds 98 out of the driveway – while Basil Pocklington was away on a business trip. At 17, he bought a 16-unit apartment building, by 25 he was the youngest Ford dealer in Canada. Four years later, he came to Edmonton and took over the country's largest car dealership. He used earnings to purchase a half-interest in the Oilers of the fledgling World Hockey Association in 1976, bought out his partner a year later, and in the fall of 1978 engineered the deal that brought Gretzky to Edmonton and changed the face of hockey forever.

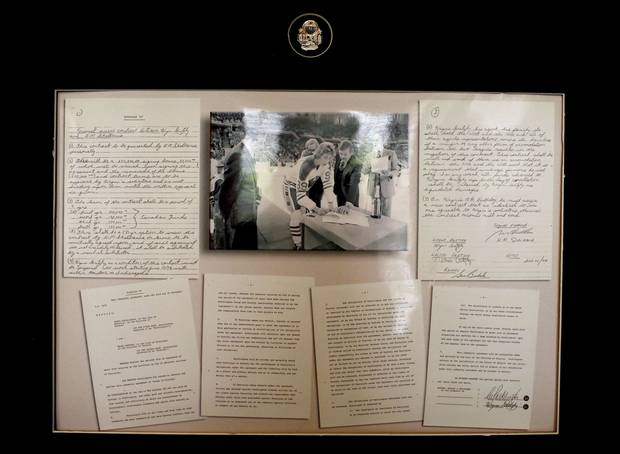

His savvy in acquiring the 17-year-old centre made the Oilers a cinch to be included in the 1979-80 merger with the NHL. In a nifty bit of sleight-of-hand, he signed Gretzky to a 20-year personal-services contract on his 18th birthday in January of 1979, a manoeuvre that excluded him from the coming expansion draft.

Most widely known for his ownership of the Oilers, Pocklington acquired and sold more than 50 companies, and once even ran for the leadership of the federal Progressive Conservative Party. At the convention in 1983, he threw his support behind Brian Mulroney, helping him become prime minister. They remain life-long friends.

A decade later, with his business empire crumbling, Pocklington gave up ownership of the club. It left his reputation in tatters, and sent the organization into a tailspin. Awash in debt, Pocklington shipped Gretzky to the Los Angeles Kings in a $15-million deal in 1988.

"I really miss the 21 or 22 years I had with involvement with the team," Pocklington says. "I loved every minute of it. Unfortunately, I got caught with a 65-cent Canadian dollar, 12.5– or 13-per-cent interest rates, and salaries went through the roof.

"I couldn't afford to do it. It was that simple."

Pocklington purchased property in California in 1998, and he and Eva have lived in California since 2002. He has been dogged by legal problems, but says he is free for now. In a 2009 affidavit, a special agent for the FBI accused Pocklington of concealing income through a labyrinth of offshore companies. That led to a perjury conviction and the seizure of many possessions, but he has since won an appeal. The Warhol prints and other valuables were returned.

"We got everything back," he says. "What they did was wrong. I have to say that civilly I prefer Canada. If not for the weather, we wouldn't be here.

"The problem down here is frontier justice. In Canada, if you sue somebody and lose, you have to pay. Here, there is 10 times per capita the number of lawsuits, and that creates ill will and increases the cost of doing business.

"Good old Canada, you can't beat it."

He wears the badge of eccentricity like an honour. He was once unsuccessfully sued for $7-million by a psychic with whom he consulted over business and personal affairs. After being kidnapped and accidentally shot by police coming to his rescue, Pocklington gave money to his assailant to help him start a small business.

Pocklington rests in hospital after he was accidentally shot by police during a hostage taking in 1982.

CANADIAN Press

He had a chef and barber in his office in Edmonton, wagered thousands of dollars playing backgammon with well-heeled associates, and is an unabashed believer in the hereafter.

"I know this is not the last roundup," he says. "Your spirit goes on and on. You meet too many people who are old souls. You know it instantly."

As gregarious as Pocklington is, his wife, who moved to Edmonton from Yellowknife at age 12, is reserved. She declines most interviews, leaving him to answer questions.

They met in 1974 and were married three months later. They went to a steakhouse on their first date. He was so smitten that he flew unannounced to Honolulu a week later to see her as she was visiting a friend.

"I went to the airport in Edmonton and with no baggage," he says. "I figured I would get whatever I needed when I got there. I told her, 'You aren't getting away from me,' and I got the girl.

"It was serendipity. When lightning strikes, you have to be ready it grab it."

He pauses and laughs.

"I am a bit impetuous," he says.

Between errands, Eva smiles as she recalls him tracking her down in Hawaii.

"He was in a suit and had no luggage," she says. "I wondered what I was getting myself into. If one of my children got married three months after meeting someone today, I would be furious."

He once brought a duffel bag stuffed with $100,000 into the Oilers dressing room and dumped it on a ping-pong table before a playoff game. He told the players the money was theirs if they won – and they went out and trounced the Kings.

"They gave everybody a piece of the action," Pocklington says. "It was a real party. Some asshole leaked what I did to the NHL. I got fined $10,000 immediately."

On the night of Feb. 24, 1982, when Gretzky surpassed Phil Esposito's NHL scoring record of 76 goals in a season, Pocklington visited the Oilers' dressing room at Buffalo's War Memorial Auditorium.

"He hadn't scored at the end of the second period, so I went down there," Pocklington says. "I told him, 'Wayne, if you get three in the third, you and your girlfriend can come to my dealership and pick up a nice Mustang convertible.' "He went out and exploded. He got three goals [on three shots] and set the NHL record."

The next day, Vikki Moss got a convertible.

It is the memories he holds close to his heart

Some nights, Peter Pocklington pours a glass of pinot noir, fires up a Cohiba cigar, and reminisces as he stands in front of a photograph of him and Gretzky that hangs above his bar.

The picture was taken on the night in October, 1984 when Pocklington presented his players with their first Stanley Cup rings. In it, the owner and No. 99 are hugging, faces cheek to cheek. Deep affection and appreciation radiate through Pocklington's smile.

Pocklington has placed most of his hockey mementoes, including his five Stanley Cup rings, in a trust for his five children and 13 grandkids. It is the memories he holds close to his heart.

"It's in the past, but believe me, I live it every day," he says. "I am egotistical enough to think I could re-create something that was going to win again.

"I hope someday after I am dead and gone that maybe I'll be inducted into the Hall of Fame for putting something on the board."

He says he and Eva were captivated as they watched the Oilers during their recent postseason run. It reminded him of 1983. That year, the Oilers roared through the first three rounds before losing to the Islanders in the Stanley Cup final. The following season, Edmonton won its first Stanley Cup.

"When we lost, [coach] Glen Sather and I and the whole team went into the dressing room and cried," he says. "It was just awful, the greatest damn low. But the next year we won, and that was the greatest high. It is what I miss about the game: the highs and lows and emotional pizzazz that excites your life.

A handwritten contract dated June 10, 1978 between a 17-year-old Gretzky and the Oilers is framed and on display in Pocklington’s California home.

Barbara Davidson /The Globe and Mail

"I try to point out that life is built on adversity. All the good times in the world don't change your direction. It is through dealing with tragedies and tough times that you grow and become a better person.

"I have learned from my mistakes."

He is happy Gretzky returned to Edmonton in a managerial position, and is glad Daryl Katz shook up the front office. The club's owner put Bob Nicholson, the long-time time head of Hockey Canada, in charge.

"In my opinion the speed of the ship is the speed of the boss," he says. "You don't grow a team like a cherry tree. It is a work in progress. They have a diamond in Connor McDavid, and have to get him polished.

"I heard that Wayne says Connor will be better than him, but he is full of crap. Connor is great, but there is nobody like Wayne. With that peripheral vision of his, he saw five ways. He was magic."

In his home office, Pocklington has framed copies of the letter he received when the Oilers were accepted into the NHL, and the contract that brought Gretzky to Edmonton.

The city's identity is forever linked with its hockey team. Even in recent years, when the Oilers fell on hard times, sell-out crowds jammed their arena.

"Edmonton is an inward-looking city, and that is all there is," Pocklington says. "It is not like Vancouver where you are looking at the ocean and mountains and can go fishing or skiing.

"In Edmonton, you chase your girlfriend or go to the Oilers game."

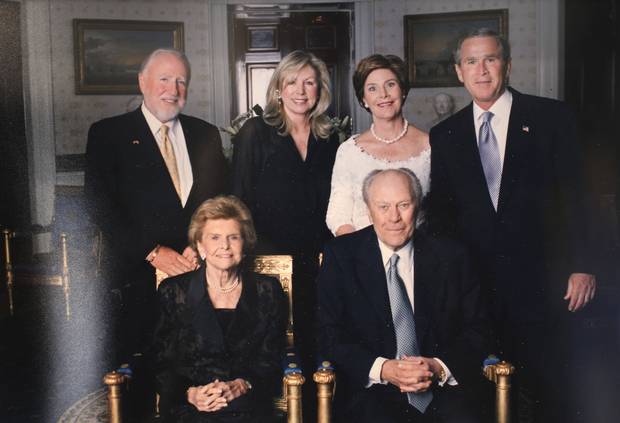

There are pictures from golfing dates with former U.S. Presidents George Bush and Gerald Ford, a snapshot of him and Eva taken at the White House during Ford's 90th birthday celebration. There is a photo of him clutching Margaret Thatcher's hand after the British prime minister had lunch with him in Edmonton.

"Eva said that if I was 15 years younger, she would have expected me to try to run away with Margaret," he says. "She was my hero, the most exciting woman I ever met."

There is a picture of him walking beside former actor and race-car enthusiast Paul Newman at a sports-car race at the Edmonton International Speedway, and an image of Sather, the Oilers former coach and general manager, being ejected head over heels from the stern of a speedboat. The two used to race together in a long-distance event on Alberta's Smoky River.

"Glen was pissed that time," Pocklington says. "I think he broke three ribs. I went into some rapids too fast. I was crazy."

Pocklington and his wife Eva with former United States President Gerald Ford, his wife Betty, and President George W. Bush and his wife Laura (top). Above, the couple pose with former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

He used to carry a 10-handicap as a golfer, but is unable to play now because his vision has been compromised by macular degeneration. The condition causes deterioration within the retina.

On the wall, there is a mounted 22-pound Arctic char Pocklington caught during a fishing trip in Nunavut. He and Sather, who is 73 and now runs the New York Rangers, used to take large groups there for excursions each summer.

"I am going to take a bunch of pals from around here and go back up in August for the first time in four years," Pocklington says. "At one point, I took 25 guys a year up there for 30 years as a business promotion. Those were fabulous times.

"My favourite passion is fly fishing. You get a 20-pound char on a No. 8 fly rod, and boy that is fun."

In one corner, A Make America Great ball cap sits on top of a shelf. Pocklington is a Libertarian, and a fan of Donald Trump. Neither Pocklington nor Eva is American and therefore could not vote in the election.

"Thank God the American people put him in office," he says. "He is going to go down as one of the greatest presidents in history. People are optimistic again. If Hillary [Clinton] had gotten in, it would have been a tragedy.

"Eva and I would have probably moved back to Canada. Wealth creation is what made America great. The demise of this country was coming on fast."

Dispute with government has lasted three decades

Peter Pocklington's house in Palm Desert is about two hours east of Los Angeles on I-10. To get there, drivers pass Desert Hot Springs, Palm Springs, Cathedral City, Rancho Mirage, Indian Wells and other enclaves fancied by snowbirds and the rich and famous.

Billboards promote the Second Amendment Gun and Ammo Store, a hydroponics grow shop and concerts at casinos starring Ziggy Marley and Joe Walsh. There is sagebrush on either side of the highway, and for miles wind farms harness the breeze in San Gorgonio Pass.

The route encompasses a stretch of the Sonny Bono Memorial Freeway and, once in Palm Desert, intersects with Gerald Ford and Frank Sinatra Drives. Ol' Blue Eyes's former estate in Palm Desert, Villa Maggio, is on the market for $3.9-million. The singer used the nine-bedroom property with a pool house to entertain fellow rat-pack members.

On Pocklington's block, landscapers fuss over well-manicured lawns. His four-bedroom house sits among a row of bungalows with multicoloured tile roofs. Cars pause to let golf carts pass.

The rogue who owned the Oilers lives in a $1.8-million home in a private subdivision. The surroundings are nice, but it is not the Vintage Club. There, golf memberships cost $250,000, and fancier homes list for $13-million.

His eyes dance as he talks about his remarkable and somewhat incorrigible past. The dispute with the Alberta government over interest payments has lasted nearly three decades. There have been seven premiers and eight elections during that span.

Pocklington says he negotiated a $50-million, no-interest loan from the Alberta Treasury to help end a bitter 6 1/2-month strike by 1,080 workers at his Gainers meat-packing plant. He contends the government changed the terms of the deal, and has been charging him 11.5-per-cent compound interest. As they have argued, his interest has ballooned from $2-million to $17-million.

"They are trying to get away with something nobody else could," he says.

He was larger than life when his Edmonton teams dominated the NHL, and on this afternoon it seems like he still is.

He muses about returning to hockey.

"I say to myself, 'Goddamn it, Peter, grow up! You really want to get back into that cesspool?' "I love the players, I love the contact, I love to win. The problem is the damn players' agreement. Minimums and maximums … it just doesn't work. Because of that, there is probably less than a 50-per-cent chance that I will do it, but I sure would love to. I miss being with the guys. We had a hell of a run."

He is fine living outside the spotlight.

"The high-profile stuff is enticing when you are young and you want everyone to love you, but the opposite happens," he says. "The press built me up and then spent 20 years destroying me.

"It is much nicer to hide down here."