Alana Paterson

To talk about women's athletics one has the obligation to start on the U.S. Senate floor in 1972. A young democratic Senator named Birch Bayh, who had been working on several constitutional issues for women's rights, brought a bill to the floor that would ultimately change history. He was to be the father of the Title IX bill that stated that "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

The top-earning female in hockey takes home a salary of just $25,000 (USD). Compare that to the top-earning male hockey player, $14-million, and you may just be looking at the largest pay gap in the world.

Alana Paterson

Canada's top 11 Olympic hockey medal earners are female. Jayna Hefford and Hayley Wickenheiser are tied for first place as Olympic hockey medal winners.

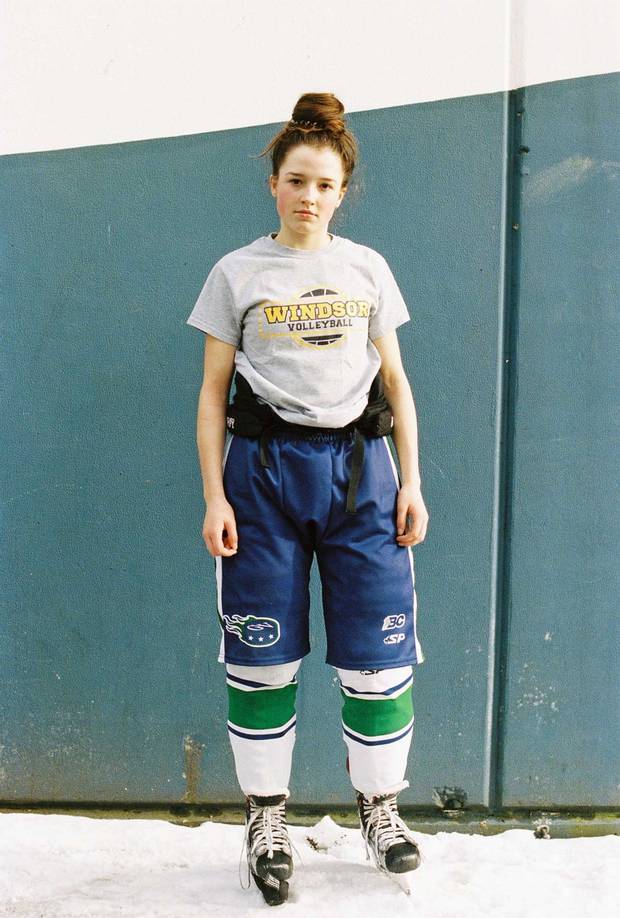

Katelynn Cain, 17, linesman with British Columbia Amateur Hockey Association (BC Hockey).

Alana Paterson

Alana Paterson

Cassie Shokar, 17, and Brooke Vial, 18, of the Greater Vancouver Comets

Alana Paterson

Alana Paterson

When girls who had made it past the age of a typical dropout were asked why others had left the game, a myriad number of reasons were given, but there were some common themes: Peer pressure from other girls (to be skinny instead of strong, or to be more feminine and focus on attracting boys); pressure from boyfriends to quit because hockey takes up so much time (and it's not a viable career choice anyway); girls being more sensitive to criticism than boys who don't take upsets home with them after the rink (another way you could say this is that hockey coaching is tailored specifically to boys' and men's reactions to authority, discipline and criticism); but above all and something every locker room said was a factor —there was no financial future for them in hockey.

ALANA PATERSON

Nina Jobst-Smith, 16, of the Greater Vancouver Comets.

Alana Paterson

Up until Title IX succeeded on the U.S. Senate floor in 1972, 1 per cent of athletic budgets were given to females including scholarships, travel and other funding. After Title IX, female enrolment immediately went up 600 per cent. In Canada, where we don't have Title IX specifically, but more or less follow a similar statute under our human rights legislation and have fairly strict athletic gender equity policies in our education system, things more or less followed a similar path to the United States.

Alana Paterson

Kaya Brossard, 17, and a teammate of the Pacific Steelers.

Alana Paterson

The story of women's hockey is a tale of unimaginable progress while at the same time only scratching the surface of how far there is to go.

Alana Paterson

Since the first female hockey world championships in 1991, female hockey enrolment has gone up more than tenfold, from more than 8,000 in '91 to about 85,000 by 2010.

Alana Paterson

Former Canadian prime minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau once said: "Canada is a country whose two main exports are hockey players and cold fronts." It was a joke of course; our main exports are timber products and apologies, but it does exemplify the seriousness of the situation. And yet, despite how progressive Pierre was, I'd still bet my last loonie that even he had no idea that, not too far in the future, his comment would not only be referring to men's hockey but to a league of women who are progressing and pushing their sport into one of the fastest-growing in North America.