In an undated photo, Neil Puckett, a PhD student from Texas A&M University, is shown holding a juvenile mastodon’s limb bone at an archeological site in Florida.

BRENDAN FENERTY

With sharpened stone knives, they knelt by the mastodon carcass and worked to dislodge one of its massive tusks, perhaps seeking to scoop out the rich pulp they knew they would find deep in the exposed socket.

They were far inland, having either tracked or come upon the giant beast by the side of a prehistoric pond. They may have been accompanied by dogs.

That is the tantalizing snapshot of the lives of some of North America's earliest inhabitants now emerging from a watery sinkhole in the Florida Panhandle.

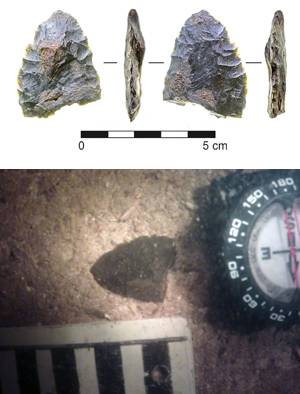

In what researchers are calling "a major leap forward" in the effort to reconstruct the peopling of the Americas, a collection of stone tools and mastodon bones long submerged and buried beneath the Aucilla River has proved to be the earliest evidence yet of human presence in the southeastern United States and one of the oldest archeological sites in the Western Hemisphere.

Thought to indicate an ancient site where paleo-hunters butchered or scavenged a felled mastodon, the discovery also includes new information about the relationship between North America's first people and its largest animals.

Radiocarbon dating of the site, known as Page-Ladson, suggests the artifacts were deposited about 14,550 years ago, at the tail end of the last ice age – likely before retreating glaciers opened up an inland route into North America across the now-vanished isthmus that once linked Siberia with Alaska.

The timing is significant, because it means the new evidence "provides indirect support for a coastal migration into the Americas," Michael Waters, an archaeologist at Texas A&M University who co-led the excavation, said of the theory that the first people might have arrived a different way.

The new findings are described in a research paper published on Friday in the journal Science Advances.

The Page-Ladson site consists of a sinkhole 60 metres wide in the limestone bedrock that is filled with sediment and located about nine metres under water.

Researcher Valérie Brosseau of the University of Toronto makes final preparations before a dive at the archeological site.

BRENDAN FENERTY

Discovered by a recreational diver in the the 1980s, it was studied in the 1980s and 1990s, but considered inconclusive because the dates associated with it were earlier than the beginning of the accepted timeline for North American habitation.

That chronology starts some 13,000 years ago with the arrival of the Clovis people – named after a style of spear point unearthed at a site near Clovis, N.M., in 1929.

DNA evidence previously gathered from ancient skeletons and modern native Americans has suggested the first people to arrive in the new world diverged from their Eurasian cousins much earlier, but so far only a handful of sites have yielded physical evidence to support this.

Beginning in 2012, researchers in scuba gear began a fresh investigation of the Page-Ladson site, finding additional artifacts and more firmly establishing their age.

"The excavations were successful beyond our wildest dreams," said Jessi Halligan, an archaeologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee, and the lead diver.

At the time the bones and tools were deposited, sea levels were significantly lower than today, and the site, now about 11 kilometres from the coast, would have been more than 200 kilometres away.

"It probably would have been a pretty isolated pond, which means people would either have had to understand how the landscape worked very well or they would have been following the big game, like mastodons, from watering hole to watering hole," Dr. Halligan said.

Microscopic fungus spores associated with animal dung from large herbivores were also recovered in the sediment at Page-Ladson from the time of the mastodon kill and well after it, which suggests mastodons overlapped in the region with humans for another 2,000 years before they died out.

This appears to contradict a theory that the arrival of human hunters in North America triggered the rapid extinction of mastodons and other large ice-age mammals.

A partly reassembled mastodon tusk from the site.

HANDOUT/DC. FISHER, UNIV. MICHIGAN MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Grant Zazula, a paleontologist with the Yukon territorial government, agrees with this assessment.

"It's showing that people have been co-existing with these animals for multiple, multiple generations," he said. "So it's not like the mastodons were caught off guard."

Another potentially important piece of evidence found at the site may be the lower jaw of a dog, but researchers said analysis of the fossil was not yet complete.

Some researchers have continued to express caution about exactly what information can be gleaned from early sites such as Page-Ladson.

Mark Collard, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, noted that the new evidence may not show that the Clovis culture was preceded by a separate migration of people into North America, but rather that the Clovis people were around sooner.

"We have so few sites that I would be surprised if we actually captured the colonization process very well," Dr. Collard said.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

What were these camel bones doing in the Arctic, and what does it mean for climate change?

2:11