March 20: A picture shows houses in a flooded area of Buzi, central Mozambique, after the passage of Cyclone Idai.ADRIEN BARBIER/AFP/Getty Images

In the week since Cyclone Idai made landfall in Mozambique, things have only gotten worse for southeastern Africa. At least 300 people are dead, a toll that’s likely to climb as rescuers discover more bodies. Hundreds are trapped by heavy rains. The threat of waterborne diseases is rising. And because of the slow-moving catastrophe and the inability to access some of the hardest-hit areas, we may not have even begun to understand the scale of the disaster. Here’s a primer on the situation so far.

The damage

Beira, a port city in Mozambique with some 500,000 inhabitants, bore the brunt of Idai’s fury when it made landfall there on March 14. The city was hit with winds of up to 170 kilometres an hour before the storm moved inland. The flooding has created a muddy inland ocean 50 kilometres wide where there used to be farms and villages, giving credence to Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi’s estimate that 1,000 people may have been killed.

After Mozambique, the storm headed inland to Zimbabwe and Malawi, flattening buildings and putting the lives of millions at risk. Zimbabwe’s eastern mountains have been deluged and the rain is continuing. Zimbabwean officials have said some 350 people may have died in their country. The force of the flood waters swept some victims from Zimbabwe down the mountainside into Mozambique, officials said.

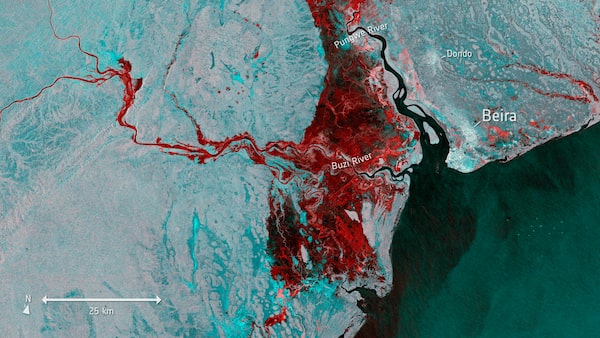

March 19, 2019: Footage from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellite shows the extent of flooding, highlighted in red, around the Mozambican port city of Beira after Cyclone Idai's landfall near the city five days earlier. Destructive rain and wind have damaged communities as far inland as Malawi and Zimbabwe.ESA/The Associated Press

Drone footage shared on social media from the International Federation Of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies shows destruction after Cyclone Idai in the settlement of Praia Nova, which sits on the edge of Beira, Mozambique.SOCIAL MEDIA/Reuters

The low-lying city is home to Mozambique's second-largest port and is a vital gateway to the landlocked countries of the region.SOCIAL MEDIA/Reuters

Locals stand beside a damaged section of the road between Beira and Chimoio.ADRIEN BARBIER/AFP/Getty Images

Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa, centre with scarf, visits the town of Chimanimani, about 600 kilometres southeast of Harare, on March 20. Mr. Mnangagwa visited a part of Chimanimnani affected by the cyclone and promised assitance in the form of food and rebuilding of homes.The Canadian Press

In Chimanimani, a family digs for their son, who got buried in the mud after the cyclone hit.Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi/The Associated Press

The humanitarian impact

Getting to the disaster zone

Sacha Myers of the non-profit Save the Children described overflowing rivers and dams, and told Associated Press that getting in aid was difficult with roads and bridges washed away or submerged. Relief efforts that were initially stifled by airport closings slowly gained steam Wednesday, and foreign governments began pledging aid to help the region recover.

Halting disease

One of the hazards flood-affected people will soon face is waterborne disease, Get Verdonck, an emergency co-ordinator with the aid group Doctors Without Borders, told Reuters from Beira:

The first thing you see when you arrive is destruction, and a lot of water. People are using well water with no chlorination, and that water is unlikely to be clean ... pneumonia and other respiratory diseases are going to be a problem.

Assessing the need

International aid has started trickling in, including US$20-million from the United Nations, with millions more from the governments of Britain, the European Union and the United Arab Emirates. “Everyone is doubling, tripling, quadrupling whatever they were planning” in terms of aid, said Caroline Haga of the Red Cross in Beira. “It’s much larger than anyone could ever anticipate.”

Ilan Noy, chair in the economics of disasters at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, told Associated Press that aid was likely to flow from dozens of countries to the African nations. How much is pledged and when, he said, correlates to the media coverage a given disaster gets, not to mention factors such as the geostrategic interests and previous colonial ties of an affected country. Ultimately, the dollar figures that are announced can bear little meaning, with the numbers typically stand-ins for the value of salaries and supplies sent overseas. “They don’t have enough helicopters or they don’t have enough doctors,” Noy offered as an example. “In that emergency phase, it doesn’t really matter how you count it. You need resources. You don’t need cash.”

Chimanimani, Zimbabwe, March 19: Members of the Zimbabwe National Army and Red Cross conduct a rescue operation for people injured in the cyclone's aftermath.Getty Images/Getty Images

Red Cross teams receive emergency shelter supplies in Beira, Mozambique, and prepare to distribute aid to survivors.SOCIAL MEDIA/Reuters

In Buzi, Mozambique, residents who fled the cyclone wait for relief aid on March 20.ADRIEN BARBIER/AFP/Getty Images

A young survivor of the cyclone looks at the damage in Beira on March 17.SOCIAL MEDIA/Reuters