Fire consumes a field in Novo Progresso, in Brazil's Para state, on Aug. 24.Leo Correa/The Associated Press

A record-setting wave of fires has been burning through the largest rainforest on Earth, many of them set on purpose in a region that Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro has reopened to development. Mr. Bolsonaro’s government, facing worldwide protests and demands from world leaders to take protection of the rainforest more seriously, has deployed military planes and fire brigades to douse the fires. The G7 bloc, and Canada and Britain individually, have pledged millions of dollars to help Brazil keep the fires in check. But Mr. Bolsonaro says he’ll reject the G7′s money until his French counterparts apologizes for remarks he claims were a personal insult.

For countries such as Canada, where climate change threatens to bring more intense fires, the Amazon’s fate offers a grim vision of the future. Here’s what you need to know.

The fires so far

The view from space

As of Aug. 25, the number of wildfires in the Amazon has surged 79 per cent over the same period last year, according to Brazil’s space research agency, INPE. Images from NASA have shown large swaths of burning land in southern Amazonas state and northern Rondonia state. Weak rainfall in Brazil is unlikely to extinguish the fires any time soon, according to two Brazilian weather experts who spoke with Reuters on Aug. 26. Bolivia is also struggling to contain big fires, many believed to have been set by farmers clearing land for cultivation.

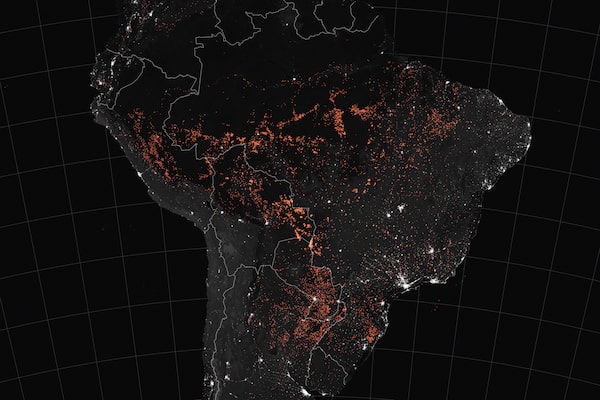

A map from the NASA Earth Observatory shows active fire detections in South America, including Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay, Ecuador, Uruguay, northern Argentina and northwestern Colombia, as observed by satellite between Aug. 15-22, 2019. - The locations of the fires, shown in orange, have been overlain on nighttime imagery acquired by VIIRS. In these data, cities and towns appear white; forested areas appear black; and tropical savannas and woodland (known in Brazil as cerrado) appear grey.JOSHUA STEVENS/AFP/Getty Images

AMAZON RAINFOREST FIRES

Fires active in preceding 24 hours,

as of Aug. 22

BRAZIL

0

1,000

KM

0

500

Amazon biome

KM

GUYANA

SURINAME

VENEZUELA

FRENCH

GUIANA

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

PERU

BRAZIL

BOLIVIA

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NASA; AMAZON GEO-REFERENCED SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION NETWORK

AMAZON RAINFOREST FIRES

Fires active in preceding 24 hours, as of Aug. 22

BRAZIL

0

1,000

KM

0

500

KM

GUYANA

Amazon biome

SURINAME

VENEZUELA

FRENCH

GUIANA

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

PERU

BRAZIL

BOLIVIA

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NASA; AMAZON GEO-REFERENCED SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION NETWORK

AMAZON RAINFOREST FIRES

Fires active in preceding 24 hours, as of Aug. 22

0

750

KM

GUYANA

Amazon biome

SURINAME

VENEZUELA

Pacific Ocean

FRENCH

GUIANA

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

PERU

BRAZIL

U.S.

BRAZIL

BOLIVIA

ARGENTINA

MURAT YÜKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NASA; AMAZON

GEO-REFERENCED SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION NETWORK

The view from the air

On Aug. 24, Mr. Bolsonaro relented to international pressure and deployed the military to fight the Amazon fires. A video posted by the Defense Ministry showed a military plane pumping thousands of litres of water out of two giant jets as it passed through clouds of smoke close to the forest canopy. But outside of Rondonia, the government had yet to provide any operational details for other states. The Defense Ministry said in a briefing on Aug. 24 that 44,000 troops were available in Brazil’s northern Amazon region, but did not say how many would be used or where and what they would do.

In a photo released by Brazil Ministry of Defense, a C-130 Hercules aircraft dumps water to fight fires raging in the Brazilian Amazon on Aug, 24.Brazil Ministry of Defense/Brazil Ministry of Defense via AP

Charcoal-making furnaces and wooden planks are seen from the air in the city of Jaci Parana, Rondonia, on Aug. 24.Eraldo Peres/The Associated Press

The view from the ground

On Aug. 26, an Associated Press team drove for hours at a stretch outside the Rondonia capital of Porto Velho without seeing any major fires, suggesting that many had been extinguished or burned themselves out since rapidly spreading in recent weeks. Many fires were set in already deforested areas to clear land for farming and livestock. Still, smoke billowed from charred fields and scrub, shrouding the sky.

A fire burns in highway margins in the city of Porto Velho, Rondonia state, on Aug. 25.Eraldo Peres/The Associated Press

Fire consumes an area in the Alvorada da Amazonia region, in Novo Progresso, Para state, on Aug. 25.Leo Correa/The Associated Press

The view from Sao Paulo

Southeast of the wildfire area lies Sao Paulo, a city of 12 million – the most populous in the Western hemisphere. On Aug. 19, the city was plunged into darkness in the middle of the day, which meteorologists attributed to the wildfire smoke and a redirected cold front that brought the smoke there and trapped it in clouds above the city.

São Paulo, 3:30 PM #gothamcity pic.twitter.com/KyR1YOGg8q

— Leandro Mota (@leandromota_) August 19, 2019

Bolsonaro vs. the world

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has faced public and global condemnation for his handling of the situation in the Amazon, where his government has dismantled decades-old environmental protections to encourage agriculture and mining. So far, he’s largely dismissed that criticism as a smear campaign, either by NGOs (who he suggested, without evidence, are setting fires in the Amazon as retribution for his administration’s reduction in their funding) or by fellow world leaders.

The Amazon was a major discussion point at this past weekend’s summit of the G7 nations, of which Brazil is not a part. The bloc agreed to a US$20-million emergency fund to fight the fires, and separately, Canada and Britain pledged a further US$24-million, as well as Canadian water bombers and logistical support. But Mr. Bolsonaro rejected the G7′s contribution, calling it an attack on Brazilian sovereignty and lobbing personal insults at French President Emmanuel Macron, one of the biggest global critics of Brazil’s response to the fires. Mr. Bolsonaro said he’d reconsider if Mr. Macron apologized for some remarks he claimed were personal insults. Brazil and other Amazon basin countries are still considering Canada’s separate offer to help, but have not officially accepted or rejected it, a spokesman for Canada’s Foreign Affairs Minister told The Canadian Press.

Mr. Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has also cast doubt on the future of a trade deal between the European Union and the Mercosur bloc, which consists of Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina. France and Ireland’s governments have said they will vote against the deal unless Brazil honours its environmental commitments. Environmental groups are also urging Canada not to sign a free-trade pact with Brazil until stronger protections for the Amazon are in place.

Mr. Bolsonaro is feeling pressure over the fires on the domestic front too. Federal prosecutors in the Amazon region launched investigations of increasing deforestation to see if the national government was negligent in the enforcement of environmental codes. Indigenous groups have also stepped up protests against Amazon resource exploitation, supported by human-rights groups such as Amnesty International.

In Rio de Janeiro, Indigenous people protest in defense of the Amazon on Aug. 25.Bruna Prado/The Associated Press

In Brussels, protesters dance as they gather in front of the Brazilan rmbassy during a demonstration organised by Extinction Rebellion on Aug. 26.Kenzo TRIBOUILLARD/AFP/Getty Images

The climate context

Wildfires are a natural occurrence in many forest ecosystems, and attributing specific extreme-weather events to climate change is an imprecise science. Since the INPE only began keeping records on Amazon wildfires in 2013, its declaration that the fires have set a record high isn’t drawing on a deep pool of directly comparable data. But unlike the recent waves of drought and fire in Western Canada and this summer’s unprecedented blazes in the Arctic, it is possible to point to specific culprits in the Amazon fires: Namely, the landowners who started many of them. On Brazil’s agricultural land, many large agribusinesses manage forests through setting small controlled fires. Though the unchecked “slash and burn” agriculture of the 20th century is officially prohibited, Indigenous nations and human-rights groups are pointing to illegal fires as the major factor in the current Amazon inferno.

In the Amazon, as in the Arctic, accelerating wildfires are part of a destructive feedback loop. The rainforest is one of the planet’s largest natural carbon sinks, absorbing about one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide every year. When it burns, that CO2 gets released back into the atmosphere, causing global temperatures to rise even further. Even if the forests were to grow back just as they were, it might not help much: A recent international study found the Amazon’s estimated capacity to absorb C02 is less than previously thought, because older research models didn’t account for the land’s phosphorus-deficient soil.

Without the Amazon to keep climate change in check, the results will be disastrous for everyone. Climate scientists overwhelmingly agree that, as human-generated greenhouse-gas emissions warm the planet, wildfires will become more common and more devastating and will start earlier in the season.

The Brazilian political context

Rio de Janeiro, May 26: Bolsonaro supporters pose for a selfie during a demonstration to shore up the ultraconservative government as it faces growing opposition.Carl DE SOUZA/AFP/Getty Images

Mr. Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist and environmental skeptic, has had a fraught relationship with the Brazilian agencies that monitor and seek to protect the Amazon. In early August, the head of INPE, Ricardo Galvao, quit his job over a dispute with Mr. Bolsonaro about deforestation data: Preliminary findings for July showed deforestation more than tripling over the same period a year ago, but Mr. Bolsonaro dismissed that as a lie. The rising deforestation also drew condemnation from international donors to the Amazon Fund, a Brazilian-run agency created in 2008 to invest in reforestation efforts. Germany and Norway withdrew millions of dollars committed to the fund, accusing Brazil of reneging on agreements to protect the forest.

The Amazon Fund was part of a decade-long push by Brazil to keep deforestation under control. From 2004 to 2014, it successfully brought deforestation down by 82 per cent. But scientists warned that the forest was in a precarious state, and critics accused the fund of being mainly a reward for gains already made, not an incentive to improve the forest further. Meanwhile, a rising global market for soybeans gave farmers more incentives to clear land for cultivation, and Brazil’s government corruption scandals of the past few years led Mr. Bolsonaro’s predecessor, Michel Temer, to appeal to rural voters to support him in exchange for eased restrictions on natural-resource extraction.

In 2017, Globe and Mail journalist Stephanie Nolen journeyed through a 2,000-kilometre stretch of Brazil’s Highway BR-163 to see the toll of deforestation firsthand. She found a region polarized between landowners and Indigenous people – and their competing visions of how to live with the Amazon:

Almost everyone I met on our journey talked about the price they were being asked to pay – to protect the forest, or to develop it. The ranchers and the farmers asked why the cost of stored carbon and recycled rain should come out of their pockets. The Munduruku [Indigenous people] wonder why their survival must be bartered for a growing economy that will fund Brazil’s pensions and universities. Should Western consumers bear some of the price, too, by paying more for sustainable rainforest products, for wooden decks or soy-based pet food or steak? Everything – wood, soy, cattle – raised on farms compliant with the Forest Code costs more, because because it comes from a reduced area of productive land on property that's mostly forest. And auditing those supply chains costs money, too.

How you can help

As noted above, reforestation in the Amazon isn’t a panacea for climate change, but it’s not a bad idea either. A study released this summer in the journal Science found that tree-planting on a massive global scale would be one of the most effective ways to mitigate the effects of climate change, and that even with existing urban and farm land, there’s room for another 900 billion hectares of tree canopy on Earth. Several charities offer Canadians a way to invest in Amazon forests, including One Tree Planted and the Nature Conservancy’s Plant a Billion Trees campaign.

Smoke billows during a fire in an area of the Amazon rainforest near Humaita, in Brazil's Amazonas state, on Aug. 14.Ueslei Marcelino/Reuters

More reading

Lloyd Axworthy and Allan Rock: Brazil’s President is committing ecocide. We must stop him

John Innes: The Amazon is approaching a tipping point. What are we going to do about it?

Marsha Lederman: In a climate crisis, artists have a duty to speak up – but what should they say?

Compiled by Globe staff

With reports from Associated Press, Reuters, The Canadian Press and Globe staff

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.