BERLIN, GERMANY - JUNE 18: German Chancellor and leader of the German Christian Democrats (CDU) Angela Merkel speaks to the media following two days of talks amongst the CDU leadership at CDU headquarters on June 18, 2018 in Berlin, Germany. Merkel has been locked a fued with German Interior Minister and head of the Bavarian sister party to the CDU, the Bavarian Christian Democras (CSU), Horst Seehofer over asylum and migration policy. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)Sean Gallup/Getty Images

The new refugee crisis is stretching the frayed ties that bind the European Union and may ultimately cost German Chancellor Angela Merkel her government.

Over the weekend and into Monday, Ms. Merkel scrambled to broker a short-term peace agreement with her coalition government’s partner in Bavaria, the Christian Social Union (CSU), which triggered the biggest threat to her reign since the start of her premiership 13 years ago.

CSU leader Horst Seehofer wants to close Germany’s borders to any asylum seekers already registered in other EU countries and, as Germany’s interior minister, has executive power to do so. Ms. Merkel, who opened Germany’s borders to more than one million refugees in 2015 and 2016, many of them fleeing the Syrian civil war, opposes the idea.

If Mr. Seehofer goes ahead, Ms. Merkel might have no choice but to fire him and bring in a more pliable minister. If she did, her three-party coalition government might disintegrate, triggering a new election and possibly a leadership race in Ms. Merkel’s party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU).

By late Monday, it appeared that Ms. Merkel has bought some time by convincing Mr. Seehofer to wait until the EU summit at the end of the month before making his final decision on whether to close Germany’s borders. By then, Ms. Merkel hopes to have the outline of a new EU-wide asylum system in place or, failing that, a series of bilateral deals with the countries on the front lines of the migration crisis – Italy, Greece and Spain. Her first bilateral meeting on Monday was with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, whose populist, anti-migrant government has shut Italy’s ports to migrant rescue ships.

In a guest column that appeared Monday in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Mr. Seehofer agreed that an EU solution was preferable but that “I must have the right to turn people away” if no solution is found. He said the EU summit must “guarantee an effective protection of the EU’s external borders and a fair distribution of residency rights, as well as a speedy return of people without residency rights.”

Ms. Merkel’s gambit may not work. Two weeks is not a lot of time to negotiate a single bilateral deal, let alone an EU-wide one. The EU has struggled for years to implement a common migration policy and has failed utterly. “I’m of the view that it will be very hard to achieve a European solution in the short- to medium-term,” Stephan Mayer, a top CSU parliamentarian told German radio on Monday.

In the absence of an EU solution, it is the national governments which, one by one, are implementing their own harsh migration policies and no one more than Ms. Merkel understands the risk to the European project of a piecemeal approach. “I see [migration] as one of the most decisive issues in holding Europe together,” she said over the weekend in her weekly podcast.

Related: What we know so far about Trump’s ‘zero-tolerance’ policy

In some countries, the politicians who advocate anti-migrant stances are rising at the expense of the centrist parties and the EU itself. The current star among the EU’s anti-migrant crowd is Matteo Salvini, Italy’s deputy prime minister, interior minister in charge of migration policy and leader of the xenophobic League party. The far-right party, in late May, formed a coalition government with the anti-establishment, though somewhat less xenophobic, Five Star Movement (M5S). Mr. Salvini, the dominant force in the populist government, even though he is not Prime Minister, used a Donald Trump-inspired “Italians first” message to propel himself to fame and power in a country that has absorbed more than 600,000 undocumented or illegal migrants in recent years.

Last week, Mr. Salvini, in an unprecedented move, stopped a rescue ship laden with more than 600 African asylum seekers from docking in an Italian port. The ship was stranded at sea for several days as it ran short of provisions. A humanitarian catastrophe was avoided when the new Spanish Prime Minister, Pedro Sanchez, allowed the ship to tie up in Valencia. Since then, Mr. Salvini has told two other rescue ships that they are not welcome in Italian ports.

It is not known whether Ms. Merkel can strike a migrant deal that would satisfy Mr. Salvini, Mr. Seehofer, her own party and the EU policy makers.

Mr. Salvini wants no more migrants, arguing that burden on the Italian state is excessive and disproportionately large among EU countries. Ms. Seehofer wants asylum seekers in Germany registered elsewhere in the EU (read: Italy, Greece and Spain) to be returned to the countries where they landed, a scenario that Mr. Salvini could never accept. Italy and the EU want an EU-wide deal that would see its migrants dispersed across the bloc. But some countries, notably Poland and Hungary, are already furious that the EU is trying to force them to take migrants they do not want.

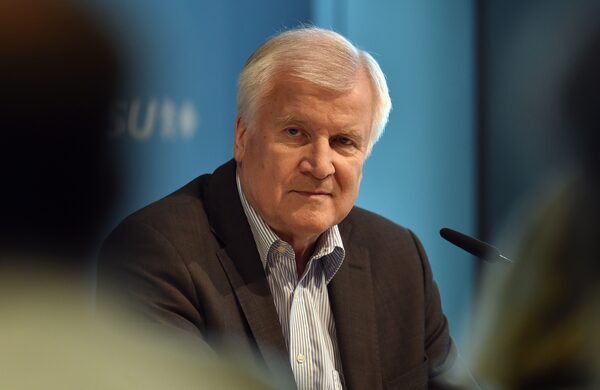

German Interior Minister and leader of the Christian Social Union (CSU) Party Horst Seehofer arrives for a press conference after the party meeting at the CSU headquarters in Munich on June 18 2018. Germany's Interior Minister vowed to begin turning back migrants at the border by July if Angela Merkel fails to find solutions with European partners, but the Chancellor rejected the threat. / AFP PHOTO / Christof STACHECHRISTOF STACHE/AFP/Getty ImagesCHRISTOF STACHE/Getty Images

Caught in the middle is Ms. Merkel. She does not want to stop migration, though certainly wants it controlled, given the political hammering she took after she opened Germany’s borders to the Syrian refugees in 2015. As the champion of the European integration project, her goal is to keep the Schengen system of internal EU borders open. If the borders are closed, she fears that an EU already buffeted by nationalist forces could reach a breaking point. On Monday, she told reporters that “the European project is at risk.”

Francesco Galietti, chief executive officer of Policy Sonar, a political consultancy in Rome, doesn’t see how Ms. Merkel can pull off an easy win on the migration front, given the wildly divergent views across the EU. “Merkel has a lot to lose; Italy does not,” he said. “For Italians, Schengen is already mostly dead because France and Austria have closed their borders to migrants coming from Italy.”

In the meantime, the pressure on Ms. Merkel is proving relentless. At stake is not only her own government but her legacy as a uniting force. Might the woman who prevented the EU and the euro zone from shattering at the height of the European debt crisis in 2011 and 2012 see the migration crisis pull the EU apart? She might, much to the delight of the anti-migrant populists not just in the EU, but also in the United States, chief among them Donald Trump.

In a Monday tweet, Mr. Trump, himself under pressure for the policy of separating children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexican border, attacked Ms. Merkel and her migration stance. He said “the people of Germany are turning against their leadership as migration is rocking the already tenuous Berlin coalition” and that “crime is way up” because of the wave of migrant arrivals.

Crime, in fact, is at the lowest level since 1992 in Germany. But never mind. Ms. Merkel has better things to worry about than Mr. Trump’s tweets. The EU is on the cliff edge once again and she needs to figure out a rescue plan, fast.

Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly