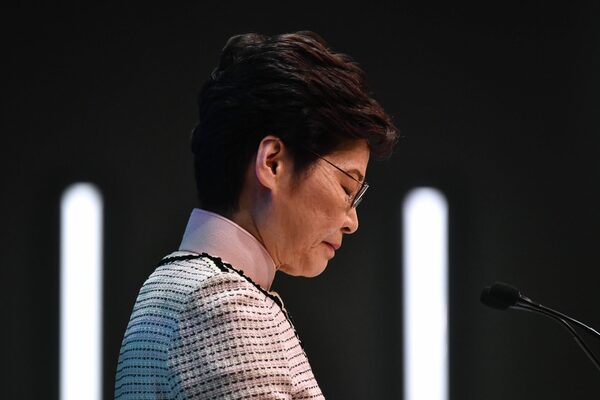

Hong Kong's Chief Executive Carrie Lam speaks at a news conference in Hong Kong, on Oct. 16, 2019, after she tried twice to begin her annual policy address inside the city's legislature.ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP/Getty Images

Hong Kong’s top political leader has promised more housing, new ferries, toll-free tunnel routes, expanded subway service and even construction of an artificial island to expand available land in a big-spending policy address intended to relieve some local pressures after more than four months of protests.

The Asian financial centre is “now facing the most formidable challenge since the return to the Motherland,” Chief Executive Carrie Lam said Wednesday, speaking between a Hong Kong flag and the Chinese national emblem. Plagued by street turmoil, the city has fallen into a technical recession, she said. But if it can “stop violence in accordance with the law and restore social order as early as possible, Hong Kong will soon be able to emerge from the storm and embrace the rainbow.”

Yet, the lengthy speech, delivered by prerecorded video after chanting lawmakers with placards disrupted Ms. Lam’s attempt to speak in the city’s legislature, made no reference to key demands by protesters, who have sought an independent inquiry into police conduct, an amnesty for people arrested on rioting charges and greater democratic freedoms through the granting of universal suffrage.

Ms. Lam begged for calm. “People are asking: Will Hong Kong return to normal? Is Hong Kong still a place we can live in peace?”

An answer came hours later. On Wednesday evening, a group of men armed with hammers attacked Jimmy Sham, convener of the Civil Human Rights Front and one of the most visible faces of the protest, leaving him blooded and lying on the street.

It was a vivid illustration of a simmering content that Ms. Lam’s speech sought to address, although critics said she avoided solutions to the most central issues.

In her speech, Ms. Lam mentioned “development” 48 times, with an emphasis on construction and infrastructure expansion measures that she called a “very bold” attempt to fix problems related to housing, land supply, livelihood and economic development in a city that ranks as one of the world’s least affordable. Her plans include seeking to install public housing on roughly 450 hectares of brownfield sites, much of it privately owned, unproductive agricultural land that could be seized by the government to build 10,000 transitional homes in the next three years. She also raised the lending cap for first-time home buyers.

The plans struck some as a set of governance solutions familiar in mainland China – heavy on construction, bereft of political concessions – that are now being used in hopes of buying peace in Hong Kong.

“Carrie Lam runs Hong Kong according to what the Beijing mouthpiece tells her to,” said Kenneth Chan, a political science scholar at Hong Kong Baptist University, referring to two state-run Chinese newspapers.

On Wednesday, the Beijing-controlled Wen Wei Po newspaper published an editorial saying the outbreak of violence in Hong Kong “is directly related to the inability to resolve deeply rooted contradictions in Hong Kong, such as limited supply of land and housing, the disparity between rich and poor, and difficulties in upward mobility for young people.”

But local scholars have in a series of reports over the last few years concluded that the primary worry for the city’s youth, in particular, is political rather than economic. Last week, researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong released a survey that showed 42.3 per cent of residents “would emigrate if they had the chance,” a significant increase from last year, with the most important reasons being “too much political dispute/social cleavage” and “no democracy in Hong Kong.” Overcrowded living conditions were the fourth-most important factor. (Canada was the most popular destination for those looking to emigrate.)

“Everybody knows that land and housing issues are no panacea to fix broken politics,” Prof. Chan said.

Local media carried reports suggesting that some of the proposals – including the higher lending cap – could actually worsen housing affordability, citing a sudden 5-per-cent to 10-per-cent rise in the price of some listed homes Wednesday afternoon.

Ms. Lam, who titled her address “Treasure Hong Kong, our home,” acknowledged that her proposals were not the answer to the recent turmoil in the streets. It “is just the beginning,” she told reporters, before rejecting one of the worries that have brought millions to the streets since June.

“I do not agree or submit to the view that Hong Kong’s rights and liberties and freedoms have been eroded in whatsoever way,” she said. Rather than an inquiry into police conduct, she promised an independent “examination of the social conflicts in Hong Kong and the deep-seated problems that must be addressed,” led by community leaders, experts and academics.

But her solutions won’t “cut much ice,” said Emily Lau, a former politician who is now a director with the China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group. Housing solutions “won’t materialize very quickly. They may take years,” Ms. Lau said.

Indeed, Ms. Lam herself acknowledged that the Lantau Tomorrow Vision, a controversial proposal to reclaim 1,700 hectares of sea into artificial islands, could take at least 12 years to deliver new housing. (The project has faced opposition because of high costs and environmental concerns.)

“The big problem lies with people’s fear of losing their freedoms – losing personal safety, losing the rule of law,” Ms. Lau said.

And solutions taken from the mainland China playbook are unlikely to calm those worries or quell Hong Kong’s unrest, said Wu Qiang, a former Tsinghua University scholar who is an expert in Chinese social movements.

“In a word, Carrie Lam, along with Beijing, when facing Hong Kong problems, are both trying to replace politics with governance, replace democracy with authoritarianism,” he said.

Chinese leadership sees “the demands of the Hong Kong people as a subversive social movement,” he said. But the “Chinese model will never help solve Hong Kong problems. … It will only make things worse.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Nathan VanderKlippe

Nathan VanderKlippe