Tehran, Jan. 6: A mourner holds a picture of Gen. Qassem Soleimani after a funeral ceremony for him as she walks past the former U.S. embassy in Tehran, now surrounded by satirical graffiti of the U.S. flag. Days earlier, the United States killed the top Iranian military commander in an airstrike in Baghdad.Vahid Salemi/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

The chain of events that led to the downing of a Ukrainian airliner with 176 people aboard – which was allegedly struck by an Iranian missile – began with a stunning gamble by U.S. President Donald Trump.

Mr. Trump’s decision to order the assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani briefly looked like it would provoke a regionwide war in the Middle East. That possibility diminished this week as Iran claimed its “revenge” in the form of ballistic missile attacks that hit two U.S. military bases in Iraq but seemed designed to avoid any loss of life. Mr. Trump, in turn, decided not to respond to those volleys, bringing this round of hostilities to an apparent end.

While both Iran and the United States stepped back from the brink, the killing of Gen. Soleimani continues to have unexpected side effects, including the deaths of the 176 people – 57 of them Canadian citizens – who seem to have been caught in the crossfire on board Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752.

The latest: Iran admits ‘disastrous mistake’: Its military accidentally shot down Flight 752

Mr. Trump struck a triumphant note in the wake of Tuesday’s limited military exchange, crowing to a rally Thursday that he had delivered “American justice,” but little has changed on the ground so far in the Middle East.

Tehran still wields wide influence – and disruptive power – from the Persian Gulf to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and the Gaza Strip. The regime backed away this week from the idea of open conflict with the U.S., but it will continue to try to push the U.S. out of Iraq, where parliament this week asked U.S. troops to leave the country, and other parts of the region.

Where the U.S. was once acknowledged as the hegemon in the region – able to wage wars (Iraq, Afghanistan) or forge peace treaties (Israel and Egypt, Israel and Jordan) almost unilaterally – it is now just one player among many.

Washington is largely on the sidelines in Syria after Mr. Trump’s precipitous withdrawal of U.S. forces last year, with Moscow, Tehran and Ankara now settling the country’s future.

Similar events are unfolding in Libya, where Russia, Turkey and a range of other players – but not the United States – have each backed a side in the struggle for the oil-rich state.

The Persian Gulf monarchies that play host to U.S. bases are wondering today whether that alliance puts them in peril.

Mr. Trump’s administration chose not to act last year when Iran was accused of attacking Persian Gulf shipping and firing missiles at Saudi oil installations. This week, states such as Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates were threatened with retaliation if they allowed the U.S. military to use their territories to strike Iran.

Rockets are shown launching from Iran to attack Iraqi targets on Jan. 8, in an image from a state-run Iranian news agency.Iran Press/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

Of course, the decline of American influence didn’t begin with Mr. Trump. U.S. standing in the region has been tumbling since George W. Bush’s ill-fated 2003 decision to invade Iraq over its phantom weapons of mass destruction. The slope got steeper a decade later when Barack Obama backed away from enforcing his no-chemical-weapons “red line” in Syria’s ongoing civil war, allowing Vladimir Putin to step in as the country’s main power broker.

The Kremlin’s role in the Middle East is now almost as important as that of the White House. And while Beijing lacks the military presence that Washington and Moscow wield, Middle Eastern governments are increasingly deferential to China and the economic might it can deploy.

Some see the conflict between the U.S. and Iran as dating back to the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the acrimony stemming from the hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy. Many Iranians point further back to 1953, when the U.S. supported (some would say orchestrated) a coup that re-installed pro-Western Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was deposed by the 1979 uprising.

But beyond Iran’s borders, the aftershocks of the Iraq War continue to reverberate. In removing dictator Saddam Hussein and dismantling his regime, the U.S. awakened old Sunni-versus-Shiite sectarian divides inside Iraq and across the Middle East. The resulting chaos allowed Iran to emerge as the champion of Shiites in the region, building and funding a network of militias from Baghdad to Beirut.

“In my opinion [the invasion of Iraq] was the big mistake,“ said Joseph Bayeh, assistant professor of international affairs at Qatar University. “They got rid of Iraq’s Sunni regime, and Afghanistan’s Sunni regime [the Taliban], and you had this revolutionary Shiite regime in the middle. You gave them a free way to become a hegemon.”

The assassination of Gen. Soleimani, Prof. Bayeh said, was the first real American move to try to roll back the influence Iran has gained since 2003. “The U.S. doesn’t want war with Iran, but the U.S. wants to get rid of Iran’s auxiliaries, its proxies, in the region.”

Najaf, Iraq, Jan. 8: Fighters from the Popular Mobilization Forces, a militia allied with Iran, wave flags as mourners prepare to bury the PMF's deputy leader, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who was killed in the same airstrike as Gen. Soleimani.Anmar Khalil/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Most analysts expect the next phase of the contest will be in Iraq, where an Iranian-backed network of militias known as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) is already trading blows with the U.S. military. It was a Dec. 27 missile attack against a U.S. base in the Iraqi city of Kirkuk – carried out by a PMF militia – that set the current crisis in motion by killing a U.S. contractor.

The U.S. retaliated two days later with air strikes that killed 25 PMF members, and the PMF responded by mobilizing its supporters to surround the U.S. embassy in Baghdad. On Jan. 3, Mr. Trump ordered the drone strike that killed Gen. Soleimani. Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy leader of the PMF and the commander of its most feared militia, was killed in the same strike. The PMF said after this week’s Iranian missile attack that it still plans to exact its own revenge against U.S. forces in the region.

The largest asset Iran can deploy beyond its borders is in Lebanon, where ally Hezbollah is often described as a “state within a state,” especially after it fought Israel’s mighty army to a stalemate in a bloody 2006 war. Hezbollah’s political arm is one of the biggest parties in the Lebanese parliament, and its armed wing has greater capacity than the Lebanese army.

Hezbollah has held its fire so far. But should it launch its arsenal of thousands of missiles against Israel, the Israeli military has vowed to respond with overwhelming force.

Before the assassination of Gen. Soleimani, Hezbollah was on the defensive in Lebanon – the target, along with other entrenched parties, of weeks of demonstrations against the country’s corrupt, sectarian political structure.

The assassination, however, permitted Hezbollah to return to its main narrative of being a resistance movement defending the country against Israel by labelling the U.S. as the aggressor in the region. In a television address on Jan. 5, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah called Gen. Soleimani “the glue that held the ‘resistance axis’ together” – a reference to the network of Iranian allies across the Middle East. “Our confrontation has already begun, from the night of the assassination,” Mr. Nasrallah said.

Iran’s empire of proxy fighters

A network of foreign militias built by General

Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian commander killed in

Iraq by the U.S., are likely to remain Tehran’s

primary weapon in its asymmetric fight against

Washington

Government relationships with Iran

and Tehran’s proxy forces

Aligned

Neutral/hedging

Opposed to Iran

Tilting towards

TURKEY

AFGHAN.:

Liwa al-

Fatemiyoun

SYRIA

Tehran

LEB.

IRAQ

IRAN

PAL.

KUW.

PAKISTAN:

Liwa

Zainabiyoun

BAHRAIN

QATAR

S. ARABIA

OMAN

YEMEN

0

800

KM

PALESTINIAN

TERRITORIES:

Hamas, Palestinian

Islamic Jihad,

Harakat al-Sabireen

BAHRAIN:

Al-Ashtar

Brigades

LEBANON: Shiite Hez

bollah – group formed

in 1982 following

Israel’s occupation of

south Lebanon

IRAQ: Popular Mobilization Forces,

Badr Organization,

Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Kataib

Hezbollah,

Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba

SYRIA: 313 Force,

Liwa al-Baqir, Quwat al-

Ridha militias – all

linked to Hezbollah

YEMEN: Ansar Allah – 100,000-

strong Houthi rebel group –

has called forattacks on U.S.

bases in reprisal for

killing of Qassem Soleimani

Sources: graphic news; Bloomberg; ECFR; IISS

Iran’s empire of proxy fighters

A network of foreign militias built by General Qassem

Soleimani, the Iranian commander killed in Iraq by the

U.S., are likely to remain Tehran’s primary weapon in its

asymmetric fight against Washington

Government relationships with Iran and Tehran’s proxy forces

Aligned

Neutral/hedging

Opposed to Iran

Tilting towards

TURKEY

AFGHAN.:

Liwa al-

Fatemiyoun

SYRIA

Tehran

LEB.

IRAQ

IRAN

PAL.

KUWAIT

PAKISTAN:

Liwa

Zainabiyoun

BAHRAIN

QATAR

S. ARABIA

OMAN

YEMEN

0

800

KM

PALESTINIAN

TERRITORIES:

Hamas, Palestinian

Islamic Jihad,

Harakat al-Sabireen

BAHRAIN:

Al-Ashtar

Brigades

LEBANON: Shiite Hez

bollah – group formed

in 1982 following

Israel’s occupation of

south Lebanon

IRAQ: Popular Mobilization Forces,

Badr Organization,

Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Kataib Hezbollah,

Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba

SYRIA: 313 Force,

Liwa al-Baqir, Quwat al-

Ridha

militias – all linked to

Hezbollah

YEMEN: Ansar Allah – 100,000-

strong Houthi rebel group –

has called forattacks on U.S.

bases in reprisal for

killing of Qassem Soleimani

Sources: graphic news; Bloomberg; ECFR; IISS

Iran’s empire of proxy fighters

A network of foreign militias built by General Qassem Soleimani, the Iranian commander

killed in Iraq by the U.S., are likely to remain Tehran’s primary weapon in its asymmetric

fight against Washington

Government relationships with Iran and Tehran’s proxy forces

Aligned

Tilting towards

Neutral/hedging

Opposed to Iran

LEBANON: Shiite Hezbollah – group formed in 1982 following Israel’s occupation of

south Lebanon

SYRIA: 313 Force, Liwa al-Baqir,

Quwat al-Ridha militias

– all linked to Hezbollah

TURKEY

Tehran

AFGHANISTAN:

Liwa al-Fatemiyoun

IRAQ

IRAN

PAKISTAN:

Liwa Zainabiyoun

KUWAIT

PALESTINIAN

TERRITORIES:

Hamas, Palestinian

Islamic Jihad,

Harakat al-Sabireen

BAHRAIN:

Al-Ashtar

Brigades

UAE

QATAR

SAUDI ARABIA

OMAN

YEMEN

0

800

KM

IRAQ: Popular Mobilization Forces,

Badr Organization umbrella group,

Asaib Ahl al-Haq, Kataib Hezbollah,

Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba

YEMEN: Ansar Allah – 100,000-strong

Houthi rebel group – has called for

attacks on U.S. bases in reprisal for

killing of Qassem Soleimani

Sources: graphic news; Bloomberg; ECFR; IISS

While the world was mesmerized this week by Mr. Trump’s impulsive moves, shrewder and more experienced leaders were quietly moving through the back rooms of the Middle East, loosening the reins of U.S. power and expanding their own zones of influence.

One of them was Mr. Putin, who flew immediately to Damascus – where he received Syrian President Bashar al-Assad on a Russian military base in a protective show of force – and then to Istanbul in the wake of Gen. Soleimani’s death. Another was Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose talks with Mr. Putin are likely to help shape the future of battleground countries such as Libya and Syria. Also on the move was China’s special Middle East envoy, Zhai Jun, who flew into Tehran to criticize “saboteurs” – a thinly veiled reference to the United States.

A decade ago, Washington would have been looked to as the key player in deciding the fate of countries such as Libya and Syria. But as its influence fades, it is increasingly absent from the Middle East chessboard, allowing others to step in to fill the void. Fragmented countries such as Yemen and Libya have become the sites of proxy wars, where regional powers squabble for control without U.S. involvement.

The rising new players are increasingly energetic and assertive. Russia has sent military forces into Syria and mercenaries into Libya, while Turkey has deployed its own troops in both countries. Between them, they are grabbing territory and negotiating ceasefires, while the United States watches almost silently from the sidelines. China, for its part, is opting for economic power: building ports in Israel, buying oil from the Gulf states, constructing railways in Saudi Arabia and investing heavily in Iraq and Iran.

Damascus, Jan. 8: Presidents Bashar al-Assad of Syria and Vladimir Putin of Russia light candles at the Mariamite Cathedral.ALEXEY DRUZHININ/ALEXEY DRUZHININ/SPUTNIK/AFP via Getty Images

In that context, Mr. Putin’s supremely confident visit to Syria and Turkey this week seemed almost like a victory lap. The Kremlin boss is one of the few world leaders who has a friendly relationship – if not quite an alliance – with the regime in Tehran.

Mr. Putin was the first world leader French President Emmanuel Macron telephoned after learning of Gen. Soleimani’s death. This weekend, Mr. Putin will be meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Kremlin, with the Middle East expected to be at the top of the agenda. And he will return to the region on Jan. 23 to visit a memorial that Israel is erecting to mark the Second World War siege of Mr. Putin’s home city of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) – a gesture an Israeli cabinet minister told The Globe and Mail last year was intended to deepen the Russian President’s attachment to Israel.

Mr. Putin is an ambitious and ascending figure in the Middle East rivalries, especially after the U.S. announcement of a withdrawal from Syria in December, 2018. His troops have taken over abandoned U.S. bases there, while his allies in the private Wagner Group have unleashed a Russian mercenary army in Libya, helping warlord Khalifa Haftar make dramatic gains over the past year.

Istanbul, Jan. 8: Mr. Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attend the launch of a pipeline to carry Russian natural gas through Turkey to Europe.Umit Bektas/Reuters/Reuters

Mr. Erdogan is on the other side of the Libyan conflict, sending Turkish troops and Turkish-backed Syrian fighters into Libya this month to defend the besieged capital, Tripoli, from Gen. Haftar’s rampaging forces. But when he sat down with Mr. Putin in Istanbul this week, they proposed a ceasefire and seemed ready to carve up the country between them, just as they had previously reached agreement on dividing power in Syria. (The two leaders held six meetings in 2019 as their alliance deepened, and Mr. Erdogan rattled NATO by purchasing sophisticated Russian-made anti-aircraft systems.)

After his military incursions into Syria, Mr. Erdogan has made it clear that he sees Turkey as a regional power in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. This week he invoked the historic Ottoman empire, referring to Libya as “these lands where our ancestors made history.”

A range of other players – Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Jordan – have been supporting Gen. Haftar, while Turkey and Qatar are supporting the UN-backed government. German Foreign Affairs Minister Heiko Maas warned that Libya must not become “a second Syria.” But the U.S. has been largely absent from the conflict – less than nine years after it spearheaded the NATO intervention that led to the chaotic conflict of today.

Jerusalem, Jan. 8: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks at a policy conference.MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

Israel, one of America’s closest allies in the region, has watched with alarm as Mr. Trump hints at a growing desire to disengage from much of the Middle East.

Israeli leaders were quietly pleased by the assassination of Gen. Soleimani, but they were worried by the Iraqi parliament’s vote to expel U.S. troops and equally troubled by the U.S. military’s disputed letter to Iraq this week, which seemed to confirm a U.S. troop withdrawal.

“If the assassination leads to an evacuation of American forces from Iraq, as it seems now, this will be a problem for Israel,” wrote Amos Harel, a defence analyst for Israeli newspaper Haaretz, in a commentary this week.

The assassination could encourage Tehran to again expedite its nuclear program – which is precisely what the Iranian leadership has vowed to do in the wake of the killing.

“The Islamic Republic of Iran's nuclear program no longer faces any operational restrictions,” read a statement carried by Iran’s official Mehr news wire. “From here on, Iran's nuclear program will be developed solely based on its technical needs.”

Though Mr. Trump has made himself into a champion of Israeli interests – recognizing its 1982 annexation of the Golan Heights from Syria and moving the U.S. embassy to the disputed capital of Jerusalem – his unpredictability is a concern. “It’s hard to say whether Israel can be certain of an American willingness to act to prevent Iran from realizing this [nuclear] aspiration,” Mr. Harel wrote.

As a long-term strategy to diversify its allies and reduce its dependence on U.S. support, Israel has expanded its commercial links with China and has discussed a possible free-trade agreement with Beijing. Chinese companies are investing heavily in Israel; two have reached deals to manage new private seaports in the Israeli cities of Haifa and Ashdod.

This, in turn, has prompted concerns from some U.S. officials, who fear the U.S. Navy might lose access to Haifa, where it often docks.

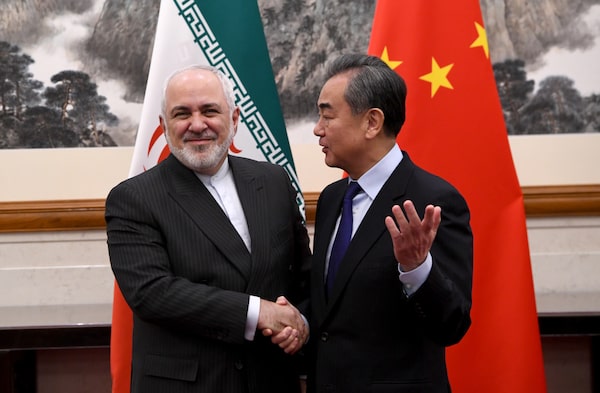

Beijing, Dec. 31, 2019: Foreign ministers Mohammad Javad Zarif of Iran and Wang Yi of China shake hands at a meeting at the Diaoyutai state guest house.Noel Celis/Pool/Getty Images/Getty Images

The decline of American influence is enabling a rise in China’s economic clout across the region. Beijing is eyeing investments in everything from ports and rail to power generation and oil and gas – infrastructure in general.

“There is only one winner in this situation: China,” wrote Minxin Pei, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, in the wake of Gen. Soleimani’s assassination.

This past fall, Baghdad signed on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its global development strategy, and ties are deepening by the month. In 2018, Iraq sent about US$20-billion of oil to China, making it China’s fourth-largest supplier.

China has also quietly imported oil from Iran in defiance of U.S. sanctions.

On the military front, last month it held its first-ever joint naval exercises with Russia and Iran in the Gulf of Oman, near the Strait of Hormuz, which the U.S. Energy Information Administration calls “the world’s most important oil transit chokepoint.”

China’s strategy is to go where other foreign investors fear to tread because of high geopolitical risk or economic and financial stress.

In the Mediterranean, the model is Piraeus, near Athens, the main Greek port. COSCO Shipping, China’s state-owned logistics giant, first invested in the ailing, strike-ridden port in 2008 and has steadily boosted its spending there over the past dozen years. Today, Piraeus has emerged as the second-biggest container port in the Mediterranean and Europe’s biggest passenger port.

It has allowed China to establish a firm foothold in a prominent European Union and NATO country, one that could be used to extend China’s influence throughout the Mediterranean, including the countries on the sea’s eastern shore.

To that end, China has bolstered diplomatic ties with Lebanon and Syria and is poised to make substantial investments (China’s embassy in Syria remained open throughout the war).

Chinese companies have already built a new quay in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli, and Chinese plans to greatly expand that port are under consideration by the caretaker Lebanese government.

Tehran, Jan. 4: A poster of Gen. Soleimani looms behind Iranians taking part in a rally against the United States.ATTA KENARE/ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

Kuwait University professor Shafeeq Ghabra says the way the recent crisis unfolded highlights the uncertainty created by the changing power dynamics.

“There is still U.S. power. There is still a role,” Prof. Ghabra said. But “you can see there is a shift in the region. U.S. power is not as it used to be. Iranian power is still there.

“This is why you see Turkey [with a military base] in Qatar. This is why you see the Chinese with a base in Djibouti.”

The region has been unsettled since Mr. Trump’s 2018 decision to pull the U.S. out of the Iran nuclear deal – known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – that Mr. Obama had negotiated with Tehran. The JCPOA saw Iran agree to limits on its nuclear program in exchange for the lifting of Western economic sanctions.

Since Mr. Trump walked away from the deal and reimposed sanctions, Iran’s cash-strapped leadership has been lashing out – including threatening shipping in the Persian Gulf – in an effort to force the U.S. to return to the terms of the agreement. In a speech from the White House this week, Mr. Trump said he wanted to negotiate a new deal with Iran, an offer Tehran said it could not contemplate while under the “economic terrorism” of sanctions.

Long-time U.S. allies now know well that Mr. Trump, in one unpredictable gesture, can and will destabilize the entire region. “There is a sense that America can push you in a certain way, but when everything falls out of order, it may not give you cover,” Prof. Ghabra said.

Toronto, Jan. 9: Mourners console each other at a vigil for those killed in the crash of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The allegation that Flight 752 was struck by an Iranian missile in the chaotic hours of Tuesday night and Wednesday morning – supported by Western intelligence that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called “clear” – raises the possibility that the current crisis has claimed dozens of innocent lives.

Still, there’s a sense of relief across the Middle East that the tensions did not spill over into open warfare – this time. (Though a senior commander in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, General Amir Ali Hajizadeh, said Thursday that this week’s missile exchange was only “the start of big operations which will continue in the entire region.”)

“We think that episode, at least, is over,” said Lowlah al-Khater, Qatar’s assistant foreign minister, in an interview at her office in Doha.

“Going back in time is just not possible. There were new factors that were introduced to the formula. Yet, there is a realization from both parties – and the other countries in the region as well – that this [direct confrontation] is a very dangerous area that needs not to be invoked.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Mark MacKinnon

Mark MacKinnon Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly Geoffrey York

Geoffrey York Campbell Clark

Campbell Clark